Slime mold oedipus?

Revisiting accelerationism, merging Dennett with Freud, mourning the posthuman future

A confession: I have never read Capitalism and Schizophrenia in full. In the golden years of the philosophy memesphere (2014-2017, RIP), it felt like you could get a pretty good introductory overview just by logging on: flat ontology, baddies without organs, kill the cop in your head, etc. In the dark, depraved days of lockdown #2, L and I considered pooling in for the OnlyFans of that Instagram catboy who promised to provide subscribers with in-depth analyses of each chapter in succession, but we never committed to the bit. When writing my MPhil, I dutifully checked out the copy held by the Cambridge UL - battered, yellow, stained in places with worryingly anonymous substances - but it remained largely unread, and was returned to the library with only minimal new stains. Alas: I had arrived at D&G too late. I was already too Hegel-pilled for the Spinozism (you couldn’t just assert your way back to a pre-critical metaphysics), too Freud-pilled for the schizoanalysis (which seemed to have nothing to do with any of the psychoses I had encountered), and probably just not French enough for the Bergsonian rhapsodies. And, yeah, it was partly because I held D&G partially responsible for the breathless high theory still languishing on in art publications and English departments: a style of writing that was ‘interdisciplinary’ only because it didn’t meet the internal standards of any discipline. But it wasn’t just that. I also suspected that the book’s politics, no less than its philosophy, had aged badly. I had read Badiou’s ‘Fascism of the Potato’ essay. I knew how taken the theory-heads of the IDF had been with the idea of the ‘nomadic war machine’. And, of course, I had come to D&G acutely familiar – from the memes, from the lore, from the samizdat PDFs – of the movement they had unwittingly seeded: new right accelerationism.

So it was somewhat humbling to recently realise that that perhaps my Wikipedia-tier comprehension of the nature of Capitalism and Schizophrenia’s intervention had prevented me from properly understanding what accelerationism – at least in its 90s iteration – had actually been about. Another confession: I was reading a piece by Nick Land. What can I say? My wholesome weekend plans to hike in the West Highlands had fallen through, and I was feeling morose and grubby. I’d opened my copy of the Accelerationist Reader – pilfered from P’s shelf at the LRB, where I assume it had been sitting meekly since arrival in 2014 – to read the essay by Shulamith Firestone, but had been led astray by seedier offerings. It had been a long time since I’d read any Land, and what I found surprised me. For one thing, the piece was pretty orthodox in its cyberneticism, and therefore oddly similar – in theme, if not tone – to contemporary work I’d been reading in systems theory and the philosophy of ‘diverse intelligence.’ For another thing, Capitalism and Schizophrenia was everywhere: like, quoted in every passage. Now my Wikipedia-tier understanding of the accelerationist slant on Anti-Oedipus had gone something like this: D&G critique mainstream psychoanalysis for its conception of desire as lack. Desire, they maintain, is productive. Accelerationism gives this idea a big thumbs up, and adds that the way to unleash the productive forces of desire is to rush headlong into capital’s total dominion and eventual extravagant collapse. But that wasn’t quite right, I realised, or at least nowhere near complex enough. Perhaps in actuality, the accelerationist take went something like this:

Psychoanalysis can be credited with the discovery of the unconscious. The unconscious is the aspect of the human that is continuous with its biological being: the aspect which ‘civilisation’ (language, abstraction, formalization) harnesses but cannot extinguish. But after the psychoanalytic revolution came the no less revolutionary rise of cybernetics. Cybernetic theory claims that biological and machinic processes are functionally equivalent. Why? Because both are feedback-sensitive, self-regulating, teleonomic forms of information-processing. Homeostasis; free energy minimisation; repetition; drive. Cybernetics suggests that the unconscious, the aspect of the human that is latently animal, is also machinic. Some early psychoanalytic theory seems to recognise this: the unconscious is frequently associated with ‘automatism’. Yet, in the main, psychoanalysis remains a fundamentally humanistic discipline. For here is where cybernetics and psychoanalysis clash: the latter recognises aspects of human psychology that are not unconscious, not machinic, not animal. Psychoanalysis disrupts the long arc of post-Cartesian modernity with its discovery of the unconscious, but it sits in tension with the techno-theoretical developments of the twentieth century due to its inability to relinquish a Cartesian vision of the conscious self: representational, reflective, meaning-making.This conscious ego is in the psychoanalytic vision newly embattled – a mirror, a froth, an excess, perhaps even an illusion; but still, it is there.

Accelerationism recognises this attachment as humanist sentimentality. Perhaps this model of consciousness never existed; perhaps it existed fleetingly and will soon be engulfed. ‘Accelerationists want to unleash latent productive forces.’ The triumph of the machine is the triumph of the animal is the triumph of the unconscious. Evolution is not Hegelian, but Darwinian; history is not a story of increasing self-consciousness (whatever might have been claimed by those crypto-Hegelian Darwinians – the early emergentists; Teilhard de Chardin), but of mutation and adaptation. There is no reason to think that consciousness is necessarily an adaptive trait. Perhaps it will die off easily, leaving nothing but a tailbone stump. And who would mourn it? The price of consciousness, as psychoanalysis itself taught us, is lack, disjunction, negativity, history. The price of history is tragedy. The future, whatever its precise contours, will be productive: posthuman, post-historical, post-tragic.

To be clear, I’m not putting this forward as a scholarly gloss on Deleuze, Guattari, or Land. I don’t know if any of them thought any of this. But I do think it’s an interesting position. In some ways, I think it’s quite close to that of a superficially extremely different philosopher: Daniel Dennett. Of course, Dennett never engaged at length with psychoanalysis (although Consciousness Explained features a few caricatures of Freudian ideas, for scenery). But he did subscribe to a broadly ‘tiered’ model of cognition in which the computational cognitive architecture common to both animal life and connectionist machines was supplemented, in humans, by something other. This otherness – human consciousness – might be an ‘evolved user-illusion’, but it’s our evolved user-illusion. In later life, Dennett would come to call one aspect of this human specificity ‘comprehension’, adopting the position – influenced by Bob Brandom – that this capacity was a fundamentally social one, ‘anchored to the practices of explaining and persuading.’ (You can make this all sound pretty Lacanian, if you go in for that kind of thing: it is only when we are inducted into the socio-symbolic order that thus consciousness, and thus ‘the unconscious’ proper, emerges.) Dennett, good Darwinian that he was, also thought that there was no reason for ‘comprehension’ to survive these contingent social practices so as to make its way into the posthuman future. In fact, he thought that all signs pointed against it. Turing’s epistemic revolution, he wrote, had been to demonstrate that ‘competence’ did not require ‘comprehension’ – that effective goal-execution, as the cyberneticists would go on to emphasise, could be a fully unconscious process. But Dennett was not by any means an accelerationist. In an interview with the Guardian to mark the publication of his last work of philosophy, he said:

One of the big themes in my book is how up until recently, the world and nature were governed by competence without comprehension. Serious comprehension of anything is very recent, only millennia old, not even a million years old. But we’re now on the verge of moving into the age of post-intelligent design and we don’t bother comprehending any more. That’s one of the most threatening thoughts to me. Because for better or for worse, I put comprehension as one of my highest ideals. I want to understand everything. I want people to understand things. I love understanding things.

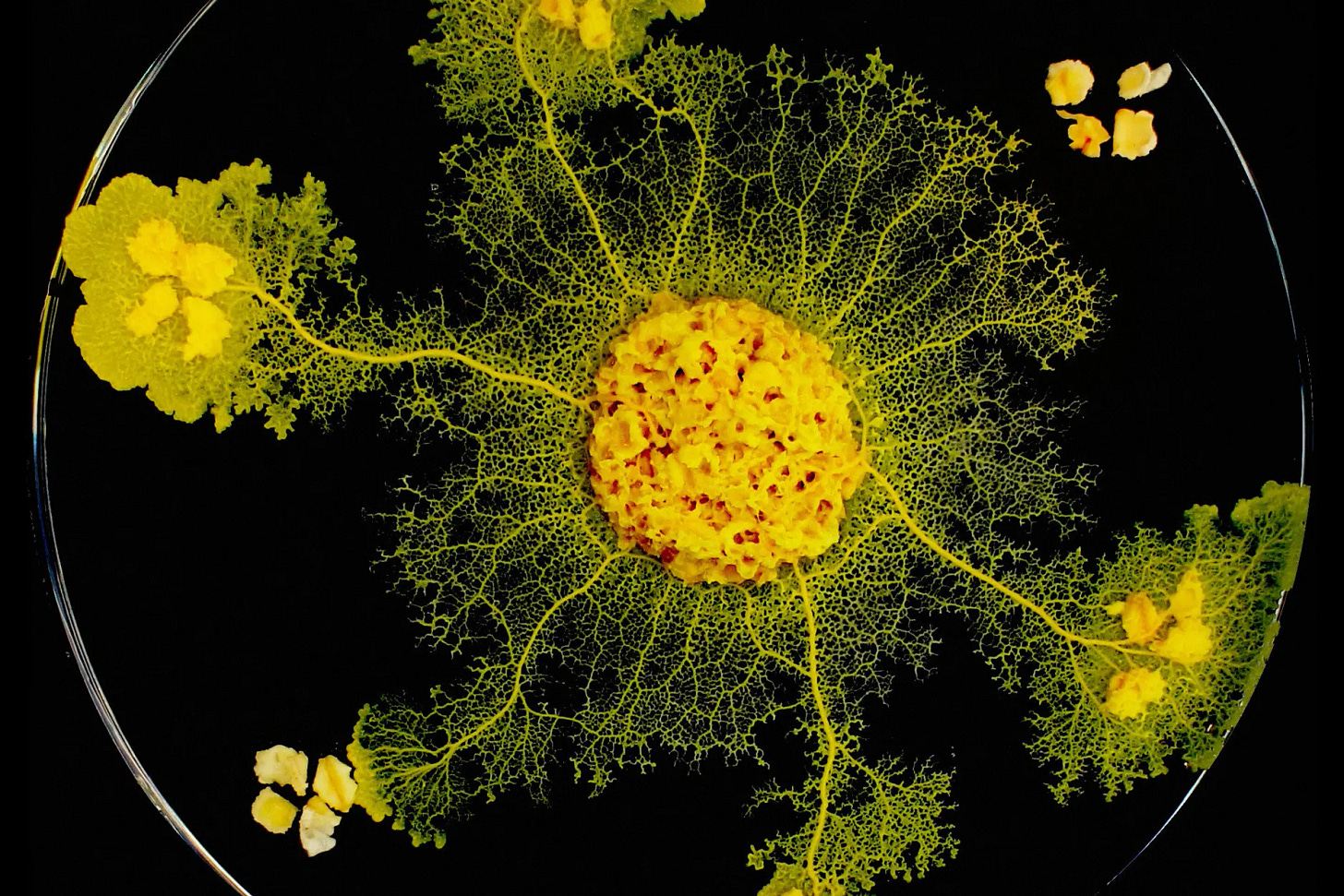

For what it’s worth, I – like most of us, I imagine – am closer to Dennett on this one than the Accelerationists. ‘Cybernetics’, Land writes, ‘is the aggravation of itself happening, and whatever we do will be what made us have to do it: we are doing things before they make sense.’ But we humans – unlike machines, animals, cyborgs, or any alien life we know of – can ‘make sense’ of our doings, however partially, poorly, or retroactively. If we judge such sense-making capacities to be valuable, this is not blind anthropocentrism: it’s valuing the continued existence of judgement itself. This is not to imply that our planet, and perhaps the universe, is not teeming with diverse intelligences, or to imply that this ‘glow of agency’ surrounding the human (to use Michael Levin’s phrase) could have emerged from anything other than processes continuous with the nonhuman (I am also a good Darwinian). But it is to say that these intelligences – to the best of our knowledge, although our knowledge is limited; for the time being, although maybe not forever – remain within that mode of cognition that for Freud was definitively non-conscious, non-historical. There is no slime mold Oedipus.

Mark Fisher described Land’s Accelerationism like this:

In a nutshell: Deleuze and Guattari's machinic desire remorselessly stripped of all Bergsonian vitalism, and made backwards-compatible with Freud's death drive and Schopenhauer's Will. The Hegelian Marxist motor of history is then transplanted into this pulsional nihilism: the idiotic autonomic Will no longer circulating on the spot, but upgraded into a drive, and guided by a quasi-teleological artificial intelligence attractor. . .

Sometimes I’m drawn towards this kind of determinism, although not to a framing that would welcome it. I have no faith that consciousness will survive into the future – which will be posthuman, whatever else it is. Perhaps Dennett was right, and comprehension is just a blip in the unforgiving plunge of evolutionary history. But if this is the case, then surely the stance to take towards this future is not acceleration but a kind of anticipatory mourning, Benjamin-style. Sometimes the death drive is taken to be the most radical aspect of Freud’s theory: its dark and sexy heart. But the death drive is dull, quotidian – literally, boring. Attaining homeostasis; maximising entropy, lowering free energy; minimising predictive surprise: these are all names for that idiotic autonomic Will. But the radical thing about Freudianism is the suggestion that in human psychology, these dynamics coexist with something else. All drives are death drives, but not all cognition is drive. In the psychoanalytic model, a dialectic is maintained between the compulsion to repeat and the flight outwards towards otherness. The thing that Dennett called comprehension is, I think, what Freud called eros, something which almost escapes his system — but not quite. I love understanding things!

It was good to meet you at the conference! From your Bluesky account I saw you had a Substack and stumbled on this fun, interesting post, which connects a bit to our talk. You should have used Q-and-A to argue that we are crypto accelerationists with Nick Land-like views!

More seriously, I hadn’t thought about a Freud connection at all, but your discussion of the death drive reminds me of one element of our talk that we passed over quickly. Nick Bostrom has argued that sufficiently intelligent AI systems will, as a result of their intelligence, seek their own cognitive enhancement. So for instance, a relatively smart paperclip maximizer should try to upgrade itself into a superintelligent paperclip maximizer, because that’s a good way of achieving its goal of making the most paperclip possible. Cognitive enhancement is a good means to almost any end an AI system might have.

If Bostrom is right about that, and we’re right that consciousness is an impediment to intelligence (it slows down performance, etc.), you get the result that even if you made a conscious AI, if it’s smart enough it will try to annihilate its own consciousness. After all, if it can make a few extra paperclips by zombifying itself, that’s the smart play.

I hadn’t thought at all about casting this in terms of a kind of Freudian death drive built into AI, but in light of your post, maybe that’s an interesting, provocative way to frame it.